![]() THE TORTOISE

TRUST HOSPITAL: A BRIEF HISTORY

THE TORTOISE

TRUST HOSPITAL: A BRIEF HISTORY

This article first appeared in our Millenium issue newsletter

Jill Martin

Jill Martin of the Tortoise Trust hospital

As this hospital report is the first of this new century, it seemed appropriate to present an over-view of some of the milestones which have taken place in our treatment of sick tortoises over the last 15 years. It has largely been a valuable learning experience for ourselves, our vets and members alike, and it has only been by observing and treating the hundreds of animals that have passed through our doors, that we are now able to advise all interested parties on an extensive range of tortoise-related topics.

During the mid-1980’s, the majority of tortoises received at the hospital had suffered frost damage in hibernation. At our small facility in Norfolk over about a three year period, we had dozens that had suffered varying degrees of eye damage, some with accompanying secondary problems such as pneumonia and liver damage.

Cesar - THE first tortoise in the history of the Tortoise Trust!

The vast majority needed daily force-feeding. Some were totally blind having presumably suffered optic nerve damage. Others having suffered lens or retinal damage had partial sight. An early hospital report records the story of Ursula, our first -ever sight-damaged patient:

“In May 1985 we received a phone call from an owner whose tortoise was experiencing difficulties emerging from hibernation. We went to investigate and found the poor animal in a truly shocking state. So dehydrated and thin that she felt like an empty shell, jaundiced and eyes tightly shut, it was obvious that without emergency treatment she would very soon be dead. As the owners clearly wanted to see the back of her, they were happy to let us take her into our care. Thus we were faced with our first very poorly patient and the monumental task of trying to salvage what little life there was left in her. It transpired that her poor condition was due to her having been frozen during two consecutive winters. During the interceding summer, Ursula had spent a miserable time tethered by a hole in her shell, blind and unable to feed. The second freeze had brought this already debilitated animal close to death. Her treatment was intensive for many months and we were despondent about her at times as she would not move. However, during the second summer with us, she one day decided to get up and walk, very slowly and shakily at first, but at least it was the start of a new phase in her progress. Two years later she was diagnosed as having perfect eyes, her problems being likely due to optic nerve or brain damage.”

Ursula’s initial treatment was largely experimental, and she received copious doses of concoctions of water, vitamins and Colovet (an iron solution), as well as tubes of baby food. Fortunately, it worked! After this point as other patients flooded in our vet advised the use of Hartmann’s solution by tube until the kidneys are functioning, followed by a rehydration solution, then on to a liquid feed, at that time Duphalyte which is excellent and still available. We have always stuck to this regime with a severely dehydrated tortoise the only difference being that there are now other liquid feeds available such as Reanimyl and Pronto Joule, the latter being used very recently to great effect, on a sick T. kleinmanni.

In the autumn of 1986 the handbook “Safer Hibernation and Your Tortoise” was written by Andy Highfield, in order to educate owners about the correct way to manage hibernation and prevent tragedies from taking place. We believe this book has saved innumerable lives, and tens of thousands of copies have been given away free.

Ruptured ear abscess - box turtle

One common condition that we have always seen is the ear abscess. Back in the 1980’s it was usual for the cheesy matter in the ear to be surgically excised, and then for the scale to be sutured. However recurrences were common, as it is rare to be able to remove all the infected matter at the first go. From 1990, our new vet had a different technique where the incision was kept open so that the ear could receive a daily flushing and continual application of a topical antibiotic cream. When the ear is finally clean and heals, recurrence is far less likely.

A bad case of stomatitis (Mouth Rot): one of many such cases

A very useful antibiotic from the 1980’s was the Framycetin Anti-scour paste made by C Vet. Coming in a syringe applicator, it was easy to get into an open ear or an infected sore mouth. Unfortunately it was withdrawn from the market in the early 1990’s. However we have had equally good results using the cow’s udder treatments, again in syringes, called Leo Yellow and Leo Red.

A rare photo of our old hospital units, circa 1985

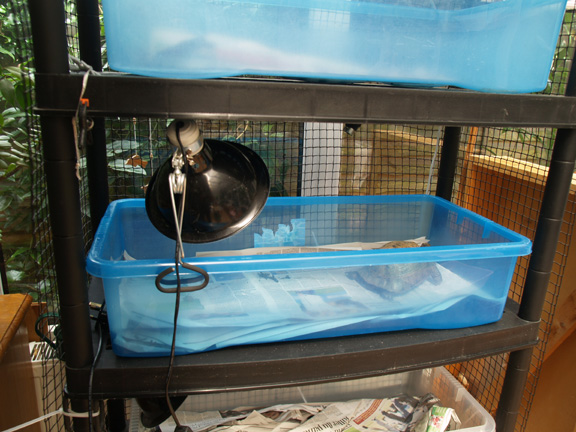

Accommodation-wise, before 1991 we had been using the closed-box type vivarium with sliding perspex doors heated by means of a spot light and under-floor tubular heater. However we became very unhappy about the lack of air-flow under these conditions and noticed that tortoises in such units often developed runny noses and dry eyes. We therefore changed to small wooden sided open-topped pens with plywood bottoms covered in floor tiles. We still usedthese units today in the hospital. They can be easily heated with a clip-on spot light and if necessary, a heat mat underneath. More recently, we changed over to PLASTIC trays based on the same concept. With these, each 'shelf' has two trays, one in use, the other out of use being cleaned. We change them over every day. This is fast, efficient and works very well!

Another area of concern has always been the high incidence of hatchlings and juveniles developing bladder stones. Again this seems to be a problem related to their accommodation. Tortoise babies kept on hard surfaces, even if they are fed correctly and offered water, are prone to developing stones. However babies given a thick natural earth-based medium to bury into are far less likely to develop the condition as their bodies will lose less moisture. We now always recommend this method of husbandry.

Around the year 1988 we began to be

increasingly concerned about the numbers of reports of cases of RNS, gut

parasites, liver disease and mouth rot, in large mixed collections, including

our own. By 1990 we observed that the

tortoises mainly affected by such symptoms were of North African origin, whilst

the Turkish T. ibera were mainly unaffected, as were the Hermann’s

tortoises. In the summer of 1990 Andy

Highfield attended an international chelonian conference in

In the autumn of 1990 we published a stark warning to all tortoise keepers in a paper entitled “Is there a Tortoise AIDS in our midst?” From our own tortoise collection we noted that “the first case subject to study was of north African origin and had a history of repeated flagellate attacks, RNS and generalised debilitation; in other words it fitted the clinical profile we are now beginning to recognise as suggestive of chelonian immune suppression syndrome. This tortoise failed to respond to treatment and finally died from pneumonia and liver failure. Immediately after death the liver was removed and subjected to histopathology. The report confirmed our worst fears; “a large number of the nuclei within the liver cells have a very dense appearance, much different to the other nuclei and this is abnormal”. In all probability “these are viral inclusion bodies”.

We still believe that the most likely

silent carriers of viral disease are the T.ibera which were imported in large

numbers from

By 1993 we still had a number of tortoises who had not been exposed to those suffering from viral problems, but who were still plagued by chronic RNS and pneumonia. However help for these came in the form of the drug Baytril, designed to cope with mycoplasma organisms as well as bacteria. One such tortoise was Beatrice, who still thrives to this day. In a 1993 report we wrote:

“this gentle North African tortoise who had been ill for several years with respiratory problems was one of the animals treated this season with the new drug Baytril. Beatrice developed the first signs of RNS five years ago, and despite treatment with various antibiotics, the condition never really cleared up. Twelve months ago she developed pneumonia coupled with jaundice and although these severe symptoms were brought under control, she still suffered from persistent rhinitis and general debilitation. More recently she developed an inability to co-ordinate leg movements, was very jumpy and refused to come out of her shell. She was treated with a twice-weekly vitamin B capsule whereupon the neurological symptoms gradually receded, and at the same time she started on a course of Baytril injections, dosed at 2.5mg per kilo, given at 48 hourly intervals. Within 10 days she had become a new tortoise. Her eyes were no longer sunken, her nose had dried and she was obviously able to enjoy life again.”

The dose rate tried with Beatrice was actually very low. We now dose at 10mg per kilo.

Baytril has helped innumerable tortoises since the mid 1990’s and is still a first choice in the treatment of many conditions. Where there has been some resistance we have had excellent results more recently, with Marbocyl (marbofloxacin) which we now highly recommend.

By the summer of 1994 we had moved to our

new site in

More sheep than people! In 1994 we relocated our facility to rural Wales

In September 1995 our new facilities were

put under pressure by the first influx of sick tortoises from a huge custom’s

seizure in

One of the rescued Libyan tortoises from 1995

However worse was to come. The winter 1995 newsletter carried the

following report: “ Two weeks after the arrival of the small Tunisian

tortoises, we received a call from Customs officers at Heathrow where a

consignment of 72 adult tortoises from

And so began the long job of rehabilitating and rehoming this large number of frail tortoises. We are obviously heavily reliant on members to offer good homes to such animals, bearing in mind that they will need a lot of rather specialised care, extra heat etc. To this day we still have some old ladies for whom homes have not been forthcoming.

Jill works with a large Algerian female

Since the coming of the Libyans, we have received many other custom’s seizures, including Leopard tortoises, Moroccan T. graeca, T. klienmanni, Tunisian tortoises, Red Eared terrapins, Leopard tortoises and Horsfield’s tortoises. We hope to help yet more in the future, and we have no doubt that the experiences of the last 15 years will continue to be drawn upon in our work to come.

(c) 2000-2002 Tortoise Trust