UNDERSTANDING

MICROCLIMATES IN CAPTIVITY

SEE NEW UPDATED ARTICLES ON THIS TOPIC ON THE NEW WEBSITE

WWW.TORTOISETRUST.COM

A major contribution to the health and normal

development of captive-reared reptiles?

Juvenile Testudo kleinmanni exploit a microclimate in sand

By Andy C. Highfield

Microclimates are used by many reptiles and amphibians to sustain themselves in otherwise unfavourable environments, and to regulate body temperature and water balance. Some well-known examples of microclimate utilization include the burrows used by arid habitat tortoises and lizards, such as Desert tortoises (Gopherus agassizii) and Spiny-tailed lizards (Uromastyx species), or the behaviour of certain toads that encase themselves in mud during the dry season.

In each case, the animal seeks to protect itself from excessively high or low temperatures, and to prevent excessive loss of body fluids from respiration and evaporation that ultimately, would lead to death from dehydration.

There is more to microclimates than temperature; maintenance of safe levels of hydration and moderation of fluid loss through skin and respiration are every bit as important.

While microclimate use is widespread in nature, in captivity, many keepers ignore this aspect of their animal’s requirements altogether, and completely fail to understand the very serious consequences for health that can occur as a result of depriving the animal of access to suitable environments where temperature and localized humidity can be self-regulated to a fine degree.

One example of how catastrophic microclimate deprivation can be for health is to be found in the case of high rates of mortality from bladder calculi (‘stones’ formed primarily of uric acid) and generalized renal failure in hatchling Gopherus and Testudo species tortoises raised under hot basking lamps on surfaces such as newspaper in glass vivaria. Although diet and the availability of fresh drinking water play a very large role in the development of this condition, environment is undoubtedly of equal importance. Twenty captive bred juvenile Testudo ibera from three separate clutches were divided into two groups. The first group was raised for two years in an indoor environment consisting of a large vivarium tank constructed of glass, with a newspaper substrate, fitted with infra-red ceramic heaters and overhead UV-B emitting fluorescent tubes. A low protein, high fiber herbivorous diet based upon wild foods was employed in accordance with the recommendations given in the Tortoise Trust’s “Tortoise and Turtle Feeding Manual”.

A hatchling Algerian tortoise half-buries itself in the described substrate, thereby regulating body temperature and reducing evaporative losses

A second group was reared using an identical diet, with identical lighting and hearting provision, but this time in an open-topped ‘table-top’ terrarium that featured a 2.5” (7 cm) deep substrate comprised of 50% sterile loam and 50% play pit sand. Additionally, some rocks, herbaceous plants and hollowed out logs were also included. It was immediately evident that the tortoises utilized this substrate extensively, often burying themselves completely overnight, or during particularly hot weather. This behavior closely mirrors that observed in the same species in the wild, where juveniles stay buried for by far the greatest proportion of their day, emerging only briefly to bask and graze.

This behavior confers several advantages to young tortoises. It conceals them effectively from many potential predators and dramatically reduces fluid evaporation from the skin and from respiration (which represent 70% and 30% respectively of total losses from evaporation). It also conserves energy by as much as 80% over energy requirements while active, and helps to stabilize body temperatures by virtue of their being in close physical contact with an infinite mass.

Adult tortoises will adopt the same strategy provided the substrate allows for this

Tortoises maintained on flat surfaces where burrowing is not possible, on the other hand, lose fluids via evaporation very quickly, their core body temperatures vary much more widely and more rapidly, and they tend to be more active. This last property is not necessarily advantageous to long-term heath, as the main increase in activity is seen in feeding. Animals reared in these conditions therefore tend to grow faster and hence are far more susceptible to developing mineral and trace element deficiencies, especially those implicated in MBD, or metabolic bone disease. In this trial, the group reared on the newspaper substrate attained a 38% greater average size than those raised on the mixed soil and sand substrate after 18 months, and their precipitated uric acid output was also visibly greater than the latter group, indicating their increased protein intake overall and their lower level of hydration.

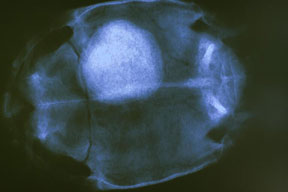

X-ray revealing huge bladder stone

After 24 months, the first case of a

bladder stone was noted in the group reared on the

non-burrowing substrate. None of the tortoises reared

on the mixed soil and sand substrate, where burrowing

was permitted, developed such problems. Subsequently,

more than 60 juveniles of several species, including Testudo kleinmanni, Testudo

graeca, Testudo ibera and Geochelone

pardalis were reared

over 4 years using substrates that permitted access to

microclimates. Not one of these animals has

developed either renal problems or bladder stones.

Growth is relatively slow, and carapace development is

very smooth and free of ‘lumps’ or ‘pyramiding’. This

compares very favorably to the growth quality and

disease incidence observed in terrarium-reared animals

maintained on substrates that do not permit burrowing.

While it may be assumed that it is only arid-habitat species that use microclimates, this is certainly not the case. Many temperate and tropical forest species make extensive use of the microclimate opportunities that exist beneath leaf litter, for example. Others burrow into moist earth, or beneath semi-rotting logs.

American box turtles also make use of moist microclimates

When designing accommodation for these species, therefore, selection of appropriate substrates is just as important as it is for desert habitat species. Where microclimate provision is not made, long term heath problems are a real possibility.

One of the Tortoise Trust's own American box turtle habitats

Further reading:

Substrate choice - Practical aspects of choosing a substrate

Feeding your Tortoise - Comprehensive dietary advice

Avoiding Problems with Box Turtles - General advice on Terrapene

(c) 2001-2002 A. C. Highfield